|

Jesuit Mission Life: Santa Cruz Bolivia Jesuit mission life was very structured. The Chiquitos missions were founded as reducciones - autonomous, self-sufficient communities ranging in size from 1,000 to 4,000 inhabitants, with two priests at their head, assisted by a council of eight native leaders (known as a cabildo) who met on a daily basis to monitor the progress of the town and its inhabitants. One priest was in charge of the “care of souls”, and cathetical instruction and the liturgy. The other was in charge of corporal matters: communal goods, land, workshops and the like.

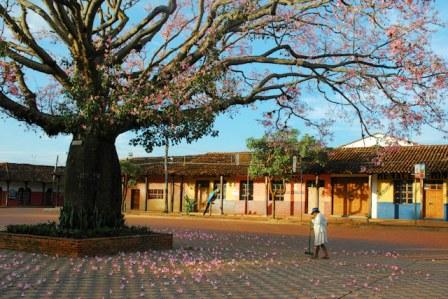

Photo © 2003-forever

Dr. Daniel Beams

Only the natives and the Jesuit missionaries were legally inhabitants. Spanish colonists were not allowed to live in the settlements, and in fact could not even remain in them for more than a few days’ time. (The sole exception to this law was the architect Antonio Rojas, who possibly constructed two Chiquitos churches.) The reducciones naturally were absolutely off-limits to the Portuguese mamelucos (slave hunters) as well, to the point where each town maintained its own Jesuit-captained private militia to ward them off. In 1696, the hated Portuguese were decisively defeated at the Battle of San Xavier - in nearby present-day San Julián - by a combined force of missionary-led Piñocas and Spaniards. There was no end to the abilities of the inhabitants to assimilate the cultural impulses of the Europeans. Soon these small villages were the cultural equals of large, urban centres like La Paz and Potosí, and had progressed to performing entire Baroque operas backed by full orchestras, complete with hand-made instruments and sophisticated musical scores...literally in the middle of nowhere. In particular, the Chiquitano and Guarayo had an astonishing ability with even the most complex music. Each settlement had it own craftsmen skilled in the various arts; this was encouraged by the missionaries as an expression of labour and love for God. The artistic abilities of the indigenous peoples were truly phenomenal. All manner of carvings, furniture, musical instruments, metal ware, and other goods poured out of these remote towns and into Spanish colonial cities elsewhere to supplement their agricultural and cattle-raising pursuits. The natives were members of one of the region’s three largest tribal groups: the Chiquitano, Guarayo, or Ayoreo. (A very few Chiriguano and Guaraní were present in some reducciones in the Chiquitania as well.) At the time of the Jesuits’ expulsion in 1767, there were at least 23,000 inhabitants, and perhaps as many as 37,000 throughout the ten settlements in the Chiquitania then under Jesuit guidance. The reducciones’ focal point was, of course, the church (templo), which acted not only as a place of worship, but also as the primary cultural, economic, and educational centre of each settlement. The reducciones’ churches - seven of which have been more or less restored to their original state - were built by the combined efforts of the missionaries and the native population (with the exception of Santa Ana, which was built entirely by the Chiquitano after the Jesuits’ expulsion). This cross-pollination had a profound effect on both sides, but more so on the natives, who gradually synthesised or adopted many of the Jesuits’ cultural influences, in particular the propensity for praising God through the arts, often in a visually and aurally ornate manner. Between 1746-1756, the Swiss Jesuit, musician, and architect Martin Schmid (1694-1772) worked in the Chiquitos missions and built there three (at least) extraordinary churches - San Rafael, San Xavier, and Concepción - from wood and adobe (sun-dried bricks) and equipped them with carved altars, pictorial works, music instruments and compositions. Seven of these templos survived for more than two centuries, despite barely durable building materials, in an unfavorable climate, with massive neglect and contrary to most other timber-skeleton churches. This was largely due to Schmidt’s solid building method. However, the churches were maintained until roughly the beginning of the 20th century with very little expenditure. The extreme seclusion of the Chiquitania stymied for a long time any attempt at modernization. Only during the rubber boom, starting in 1880, were three of the churches modified in a neoclassical style (i.e., fitted with wooden columns faced with bricks). Ten of these churches were built, of which seven still exist (one - San Ignacio de Velasco - is a not a restoration but a reconstruction). These seven comprise the commonly known “Jesuit Mission Circuit” churches of Chiquitos (although three others, those of Santiago de Chiquitos, San Juan Bautista, and Santo Corazón, also exist, albeit in a state of replacement, ruin, and decay, respectively). Remarkably, those that stand today were all built within 30 years of each other (1745-75). At least three are attributable to the indefatigable Swiss Jesuit Fr. Martin Schmid, and another two to one or more of his co-workers. The enormity of the task of building these churches is scarcely imaginable today. They did not spring up overnight: it took years of painstaking work, with every piece made by hand. For example, consider the templo at Concepción, begun in 1752. According to Schmid’s own correspondence, more than 2,000 hardwood trees were felled: each of the church’s massive beams required an entire tree trunk. These were about 12 metres (36 feet) in height, and on average weighed in excess of nine tonnes. To roof the edifice, more than 100,000 bricks and tiles were needed, and an additional 150,000 bricks for other sections of the building. The vertical columns - also of hardwood - weighed 20 tonnes. All this was done by hand, using only the crudest of tools. The result was a church that holds more than 3,000 people. So important were - and are - these Chiquitos churches that they were placed upon the register of World Heritage Sites by UNESCO in 1990. They still play a central role in the lives of the people of the Chiquitania, and to the missionaries (now mostly German, Italian, and Polish Franciscans) who continue to minister to their spiritual needs. They are at the same time parish churches - enormously large and historic ones at that - and spiritual centres for the people who live in the region and still observe many of the same rites and traditions from the Jesuit missionary era, three hundred years on. Political Considerations and the Expulsion of the Jesuits These ten settlements eventually and inevitably became caught in a political battle between Spain and Portugal, the latter of whose slave traders in nearby Brazil – the hated mamelucos - had their own nefarious purposes for expanding westward. It did not help that their thriving economies and well-ordered way of life had earned the reducciones a great deal of jealousy. And as they were virtually semi-independent states (complete with their own private militias), both powers were suspicious of the missions’ undefined political status and sought to exploit it. It all came to a sudden end on 27 February 1767, when the Spanish King Carlos III ordered the expulsion of the Jesuits from his realms (those in Brazil had been expelled in 1759), including the scarcely two dozen missionaries who watched over the enormous Chiquitania territory (most of whom soon died as a result of the hardships endured after the expulsion). With it came the end of a truly unique era in history, but one whose legacies still live on for the artist, historian, or traveller to appreciate. https://youtu.be/otGyaLpiWoo After the Expulsion The astonishing growth of the Chiquitos reducciones ended abruptly with the expulsion decree, and the towns slowly spiralled into a state of near-terminal decline. In 1776, the government of the entire region was militarised and the Chiquitania administered from the newly created, far-away Viceroyalty of Río de la Plata (to which the Audencia of Charcas now belonged). In ecclesiastical terms, the last reducción was secularised a few years after Bolivia declared independence in 1825 and the Diocese of Santa Cruz de la Sierra took over spiritual control (although in 1840 Franciscan missionaries were appointed to the Guarayos and Moxois missions). They lay in a state of economic and social torpor until the arrival of the Swiss architect and former Jesuit, the late Hans Roth, whose nearly three decades of spearheading restoration efforts finally raised them from obscurity. The swift demise of these settlements raises troubling questions for the student of colonial and post-colonial history. How could such unparalleled - and acknowledged - success so quickly turn to decay and obscurity? As key export areas, why was no support offered by the Spanish crown to maintain their economic prosperity after the Jesuits were banished? Why, after the Jesuits were reconstituted by Pope Pius VII in 1814, did the Jesuits not return to the Chiquitania? To a large extent, the blame for these matters lay with the avaricious interests and political policies of Spain, to a lesser extent with Portuguese interests, and even the papacy itself, all of whom had conspired to obliterate the Jesuits, and in so doing, their handiwork and legacy in the Chiquitania and elsewhere. As the late Hans Roth, the principle restorer of the Chiquitos missions, wrote, “It was not the natives who destroyed the work...but rather the economic and political envy, the ignorance and barbarism of those already civilized and educated.” Current Research Concerns Although the expulsion of the Jesuits is a matter well-documented, and much has been recorded of the period preceding their banishment, considerable research remains to be done on the history immediately preceding and following the Jesuit missions of the Chiquitos. (This is especially so in the case of the chaotic period immediately following Bolivia's independence.) As regards the Jesuit Era itself, almost no research has been dedicated to the anomalous churches of San Juan Bautista and San José de Chiquitos. Astonishingly, although primary resources exist in archives in Cochabamba, Sucre, and elsewhere, nothing has been written on the interaction between the Jesuits in the Chiquitos missions and their counterparts in the Moxos and Guarayos. And while there is much extant correspondence between the (mostly Central European) Jesuit missionaries and their fellow-Jesuits in Europe, little beyond a few of Schmid’s letters have been examined. As noted above, few works in any language extensively treat either the pre- or post-Jesuit era (and none in English). Thus, what little work is available focuses almost exclusively on developments of the Jesuit era only, and often relies upon secondary sources (many of them inaccurate). Some of the more vexing problems are that no exhaustive bibliography of the Jesuit presence in the Chiquitania exists (the largest being Querejazu’s, found in Las Misiones Jesuíticas de Chiquitos); a Spanish or English biography of Schmid has yet to appear; the vast archives of Hans Roth lie mostly unexamined in Concepción (in the care of his elderly widow); and much important Jesuit-era art still lies in abysmal storage conditions in San José de Chiquitos and elsewhere throughout the region. Other issues loom, of a social nature: the Chiquitos missions are not in any sense “pure” Jesuit reducción replicas. Long years of secular and Franciscan oversight have resulted in a hybrid culture, and one that is in great danger of being further diluted by the present government’s efforts to make the area a primary Bolivian tourist attraction. Ironically, this is not only precisely what UNESCO’s World Heritage designation was designed to mitigate, but it also means that further scholarly work will be made more difficult. On A Positive Note Of the original eleven Chiquitania settlements, nine survive (San Juan Bautista is now in ruins, and San Ignacio de Zamucos was abandoned early on). Of these, seven possess a unique (albeit hybrid), virtually intact cultural and social infrastructure that has changed little since the days of the Spanish colonists. All remain active settlements (several still function as missions), with vibrant religious customs and beliefs. In fact, the Chiquitania is now undergoing something of a cultural and historical renaissance, much of which has come to light only recently. With renewed scholarly interest in the area and a careful, rigorous approach to the conservation and study of the Chiquitos missions, much more can be done to both preserve and draw from the unique cultural and historical patrimony of these places. Use of this text has been graciously authorized by its author, Geoffrey A.P. Groesbeck, who has dedicated many years, clearly much love, and an entire website to this unique region of Bolivia. I strongly urge you to view Mr. Groesbeck's website www.Chiquitania.com as it is the most complete and continuously updated resource you will find anywhere on Jesuit mission life.     |